Scripted and animated character archetypes!

Time for a few notes about character and animated archetypes. Without them the reading process would be for naught. What makes them interesting, why are they fascinating, and what makes them stick in our minds and hearts? What embodiment’s do they possess which make them smart, full of feeling, what motivates them, their memories and desires, their fantasies and their foibles. In short, what makes them tick. Both their good and bad attributes are important to these decisions.

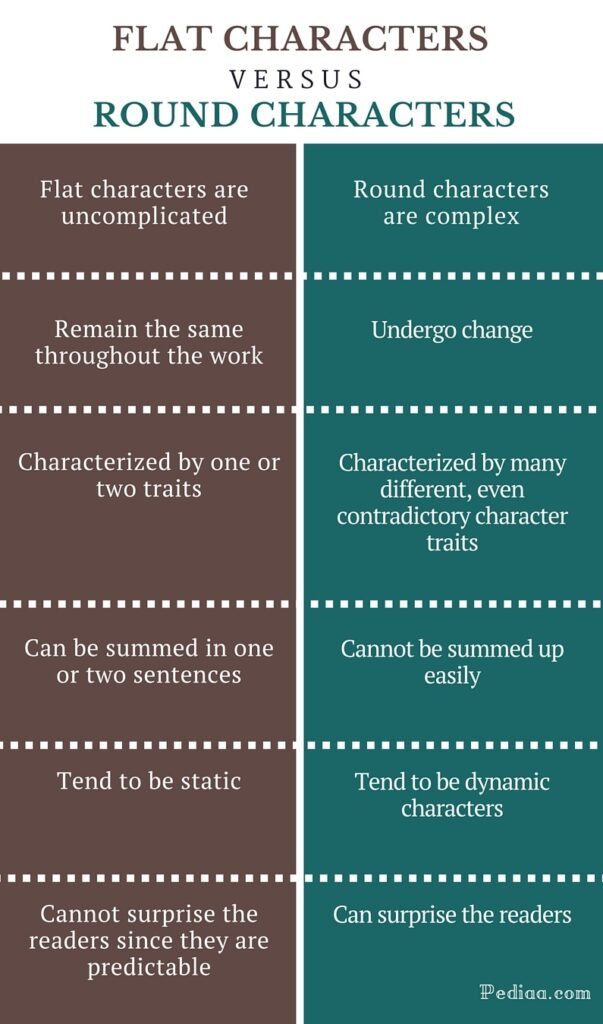

E.M. Forster gave us some distinctions to look for in his book ‘Aspects of the Novel’ to help define the process of character development.

These are the forms for lead and secondary characters:

Ever notice that niceness almost always prevails at the end of a book?

Do characters have to be perfect?

What sort of characters stand out?

Does an aspect of a flat character bring out the roundness of of the lead character?

Is the character interesting enough for you to be interested in what happens to him in the story?

What would you like to see happen to a particular character? Why?

Do the internal struggles and conflicts resolve themselves?

Does the crisis a character faces reckon itself with the past?

How do the good attributes change to bad and visa-versa?

Why are some characters round and others flat?

Does the character surprise you?

Does he convince?

Look for any juxtaposition to monitor your impressions over the course of a characters development.

Is the image of the self what you want verses what you want to want? Example being: The Ginger vs. Marianne dilemna

A few things to look for in your reading of Animated Character Archetypes.

When you start asking these questions it’ll open the door to a greater understanding of where your own character development can go through the course of your own life story. Understanding how characters develop as a reader may help tell the tale.

Are you the main character of the story of your life?

That means taking time for a little self discovery.

What if all the cognitive biases are like a novel going on in your head?

I suppose a famous novelist could have something great to say about the question at hand. I’d love to hear any of them.

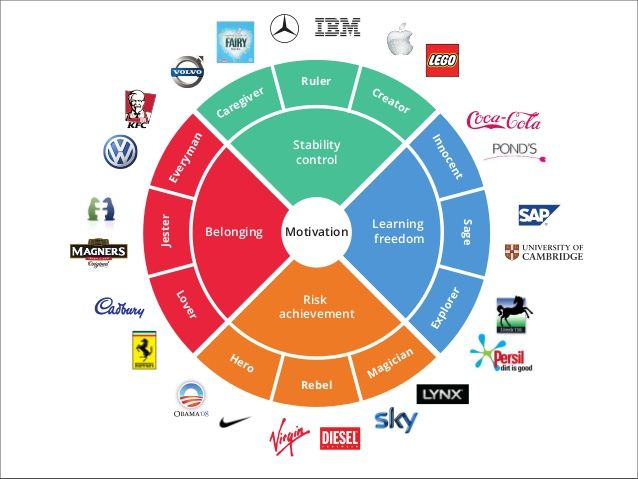

Animated character archetypes can fit certain personas to carry on specific story lines in ones life.

One for work. Another for play. And one for when you think no one is looking. As long as you manage to not lie to yourself (even with the characterizations) a certain sense of balance can be achieved. Doing your own biography and dividing it up into different phases of your life helps to slow down emotional outbursts. Knowing your own triggers and their histories and creating characters for them shapes a new form of understanding within the self. Answering truthfully to yourself why others seemed to get in the way of an instant satisfaction or a personal agenda. The stages, the ups and downs, and everything sideways and in between that comes with being too selfish.

I think understanding your own personal history helps to listen to another POV with a more patient bearing. Contingent upon one can be totally honest with oneself….at least. Very hard thing to do in this world filled with chains of desires and addictions to numerous to count. Never lie to yourself.

Honesty with others? That depends on so many factors working together. Tricky Dicky, Murphy and his cohorts, and Finnegan wake always get in the way. How many times does a person screw themselves in life by hurting another?

It also offers an array of satire to describe all sorts of ludicrous nonsense from politics to the small things in everyday life. Including everybody involved in our own little worlds. Still, many more are beginning to pay attention to larger worlds around them. Especially through the internet. The influences that control our lives. Layer by layer. The little ones, the big ones. Right on up to the top of the pyramid….grouped in categories to better serve you.

Learning to be a narrator in the story of your life helps bring a balance to things.

After all, it is just A story. One of many. Is it a good one? Is the hidden diary of your heart honest? Or is just told with fancy jargon and bloated juxtaposition bringing the victor (yourself) all the spoils of triumph without paying a price. Sanitizing the tale for future generations to follow and possibly emulate. What lies we tell ourselves to make it all better.

What are your favorite monuments in history?

How many of them do we look up to still or even remember?

How many are we going to tear down?

What about our own personal monuments to ourselves?

How narrative moved beyond literary analysis

John Lanchester offers a brief take on this phenomenon in the London Review of Books:

“Back when I was at university, the only people who ever used the word ‘narrative’ were literature students with an interest in critical theory. Everyone else made do with ‘story’ and ‘plot’. Since then, the n-word has been on a long journey towards the spotlight – especially the political spotlight. Everybody in politics now seems to talk about narratives all the time; even political spin-doctors describe their job as being ‘to craft narratives.’ We no longer have debates, we have conflicting narratives. It’s hard to know whether this represents an increase in PR sophistication and self-awareness, or a decrease in the general level of discourse.”

In 1947 it was another Brit, George Orwell, who posited a direct relationship between political corruption and the misuse of language. But Orwell’s attention was fixed on language at the level of words and phrases: the use of euphemism to veil unspeakable horrors; empty slogans meant as a substitute for critical thinking; pretentious jargon designed to lend authority to special interests. While Orwell wrote many powerful narratives – fiction and nonfiction – he showed little interest in theories of political narratives in the way Lanchester describes.

The use of narrative for political purposes was not invented in this century or even the last. It is a standard lesson of Shakespeare scholarship that the Bard’s history plays, such as the Richard and Henry plays, tilted the historical record in favor of the Tudor dynasty (the family that gave England Queen Elizabeth I), an act of political dramaturgy that provided the playwright cover and, no doubt, financial rewards.

The long journey of narrative described by Lanchester took many professional stops before it arrived so conspicuously in the barrio of spin-doctors, speech writers, and other political handlers. For decades now, narrative theory has wended its way through the worlds of medicine, law, and business management, just to name the most obvious arenas.

https://www.poynter.org/news/how-narrative-moved-literature-politics-what-means-covering-candidates